Marvin Minsky

30 Oct 2021 - 19 Oct 2025

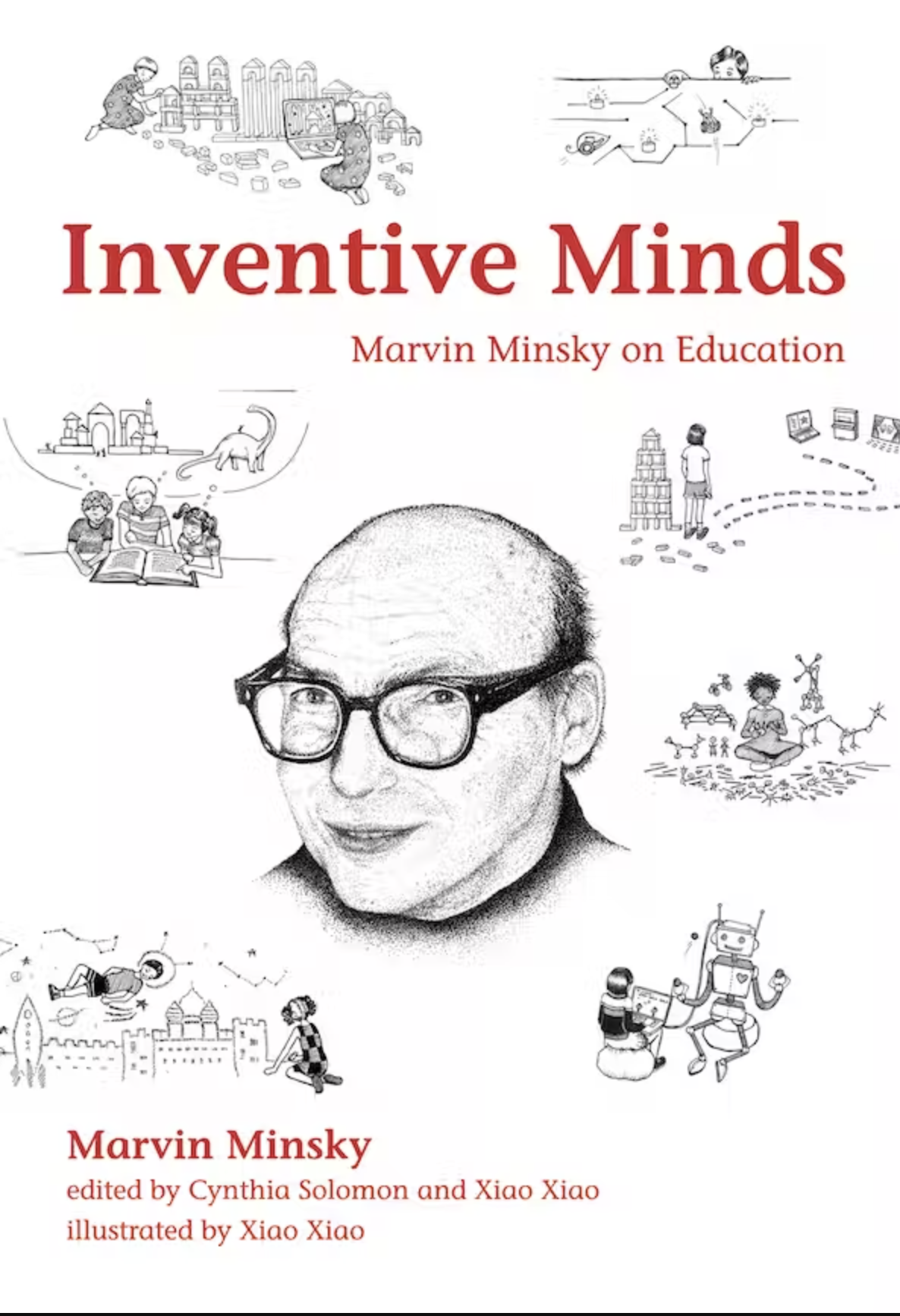

- A major influence and my advisor at MIT. I contributed an introduction to Marvin Minsky/Inventive Minds, a collection of his essays on education. That and Firing Up the Emotion Machine, a sort of eulogy I wrote after his death in 2016, are my best efforts at writing down my views of this brilliant, kind, ambitious, and flawed man.

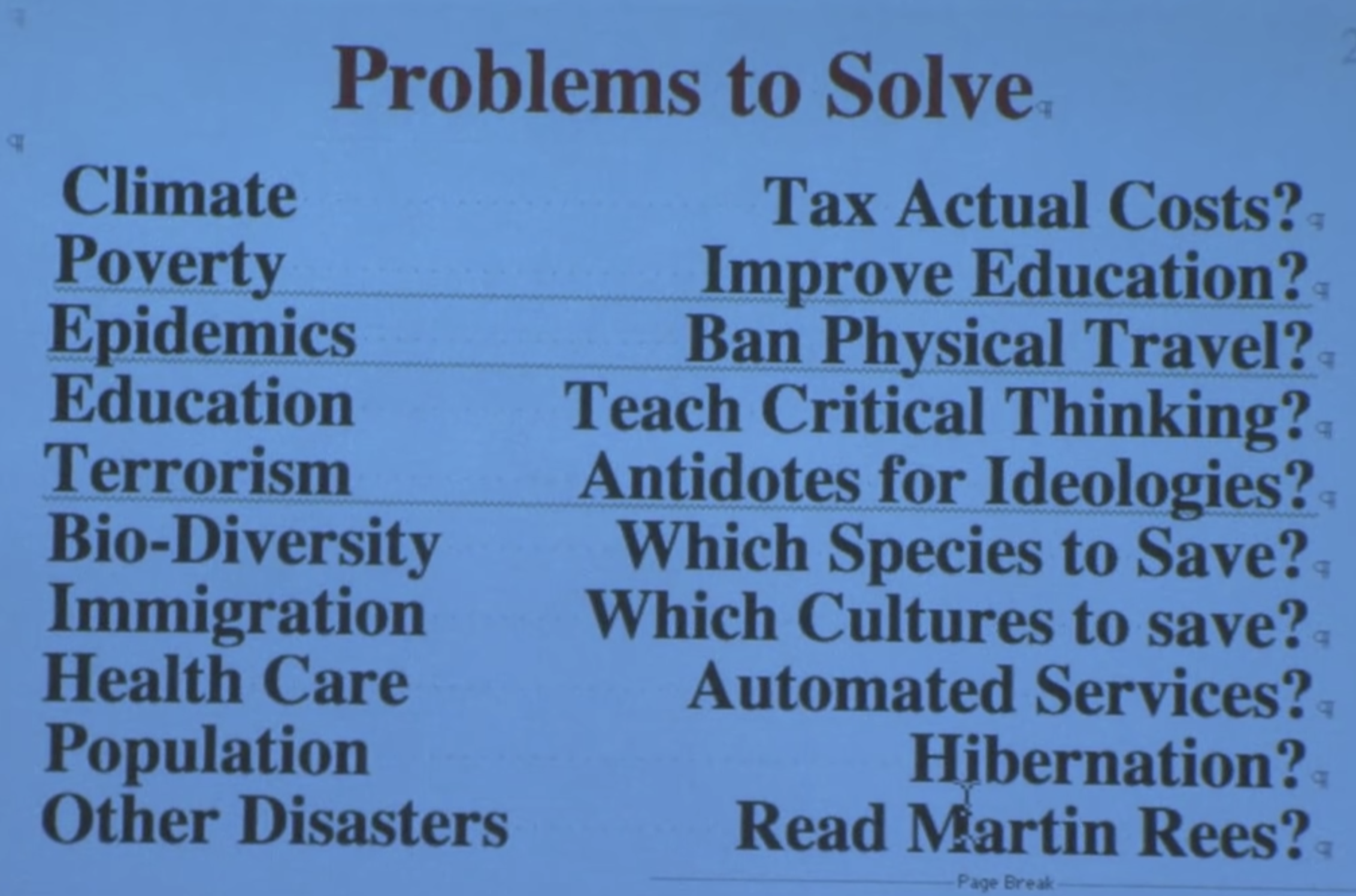

- This clip really echoed with Nietzsche's Notes on Daybreak:

In general I think if you put emphasis on believing a set of rules that comes from someone you view as an authority figure then there are terrible dangers...most of the cultures exist because they've taught their people to reject new ideas. It's not human nature, it's culture nature. I regard cultures as huge parasites.

- Gotta say that while I admire the wit of this I disagree...it's got this underlying individual vs culture stance which is kind of adolescent and philistine (and he probably doesn't really believe it, it probably is just a random sniping in the ongoing low-level conflict between science and the academic humanities that Marvin was always willing to stoke.)

- Also at 6:10, a bit more on culturally-induced cognitive blindness

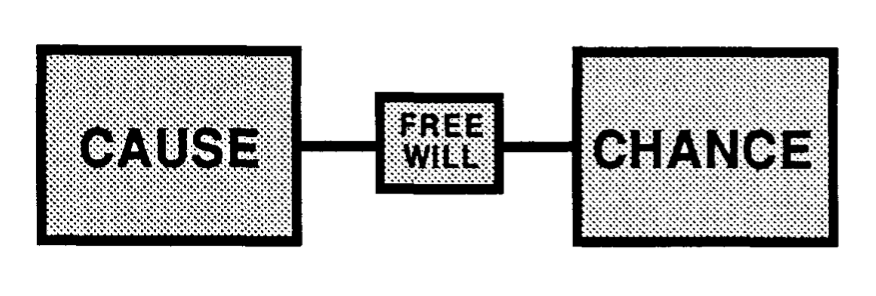

- At 7:40, in the midst of a discussion on how emotions like anger are not separate from rationality but are more like modes of thought:

There really isn't anything called rational, everything depends on what goals you have and how you got them...

- I was surprised to see that Francisco Varela et al's book The Embodied Mind, engaged quite deeply with Marvin Minsky/Society of Mind. See VTR on Society of Mind.

- This essay Marvin Minsky/True Names Afterword seemed particularly rich in nuggets relevant to AMMDI, I extracted a few below.

- On intentional programming.

I too am convinced that the days of programming as we know it are numbered, and that eventually we will construct large computer systems not by anything resembling today's meticulous but conceptually impoverished procedural specifications. Instead, we'll express our intentions about what should be done in terms of gestures and examples that will be better designed for expressing our wishes and convictions. Then these expressions will be submitted to immense, intelligent, intention-understanding programs that then will themselves construct the actual, new programs

In order for that to happen, though, we will have to invent and learn to use new technologies for "expressing intentions". To do this, we will have to break away from our old, though still evolving, programming languages, which are useful only for describing processes. But this brings with it some serious risks!.

- On AI Risk

The first risk is that it is always dangerous to try to relieve ourselves of the responsibility of understanding exactly how our wishes will be realized. Whenever we leave the choice of means to any servants we may choose then the greater the range of possible methods we leave to those servants, the more we expose ourselves to accidents and incidents.

The ultimate risk comes when our greedy, lazy, master-minds attempt to take that final step––of designing goal-achieving programs that are programmed to make themselves grow increasingly powerful, by self-evolving methods that augment and enhance their own capabilities. ...

- Marvin goes Heideggerian

Consider how one can scarcely but see a hammer except as something to hammer with

- On functional representation

An icon's job is not to represent the truth about how an object (or program) works. An icon's purpose is, instead, to represent how that thing can be used! And since the idea of a use is in the user's mind––and not inside the thing itself––the form and figure of the icon must be suited to the symbols that have accumulated in the user’s own development

- The government of the Society of Mind

Now it is easy enough to say that the mind is a society, but that idea by itself is useless unless we can say more about how it is organized. If all those specialized parts were equally competitive, there would be only anarchy, and the more we learned, the less we'd be able to do. So there must be some kind of administration, perhaps organized roughly in hierarchies, like the divisions and subdivisions of an industry or of a human political society.

- "I didn't hire people to do jobs; I hired people who had goals"

- A nice tribute from Robert Kuhn who did a lot of good interviews with Minsky and others: Brains, Minds, AI, God: Marvin Minsky Thought Like No One Else | Space