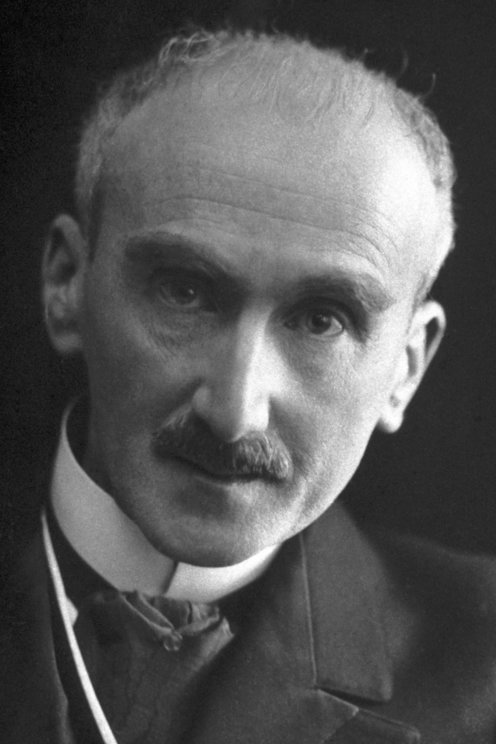

Henri Bergson

08 Dec 2022 - 15 Nov 2025

- Turns out one reason his thought became unfashionable: it appealed too much to women Henri Bergson, the philosopher damned for his female fans | Aeon Essays. And it was too Jewish:

The associations between femininity, irrationality and Bergsonism often overlapped with anti-Semitic attacks against the philosopher. In France, such attacks were coordinated by a group of thinkers affiliated with the Right-wing anti-Dreyfusard political movement Action Française. Between 1910 and 1911, Pierre Lasserre, the main literary critic for the movement’s newspaper (also Action Française), published a series of anti-Bergsonian articles. He painted Bergson’s philosophy as excessively sentimental and vague and, in his final article, asserted that Bergson would never reach the level of an Aristotle or a Leibniz because he was Jewish.

Bertrand Russel on The Philosophy of Bergson)

M. Bergson’s philosophy, unlike most of the systems of the past, is dualistic: the world, for him, is divided into two disparate portions, on the one hand life, on the other matter, or rather that inert something which the intellect views as matter. The whole universe is the clash and conflict of two opposite motions: life, which climbs upward, and matter, which falls downward. Life is one great force, one vast vital impulse, given once for all from the beginning of the world, meeting the resistance of matter, struggling to break a way through matter, learning gradually to use matter by means of organization; divided by the obstacles it encounters into diverging currents, like the wind at the street-corner; partly subdued by matter through the very adaptations which matter forces upon it; yet retaining always its capacity for free activity, struggling always to find new outlets, seeking always for greater liberty of movement amid the opposing walls of matter.

But among animals, at a later stage, a new bifurcation appeared: instinct and intellect became more or less separated. They are never wholly without each other, but in the main intellect is the misfortune of man, while instinct is seen at its best in ants, bees, and Bergson. The division between intellect and instinct is fundamental in his philosophy, much of which is a kind of Sandford and Merton, with instinct as the good boy and intellect as the bad boy.

- OK he's getting snarky now.

Instinct at its best is called intuition. “By intuition,” he says, “I mean instinct that has become disinterested, self-conscious, capable of reflecting upon its object and of enlarging it indefinitely"

- That's interesting, not the usual meaning of intuition I think.

His doctrine of time is necessary for his vindication of freedom, for his escape from what William James called a “block universe,”

- Did not know James had IP on that concept.

One of the bad effects of an anti-intellectual philosophy, such as that of Bergson, is that it thrives upon the errors and confusions of the intellect. Hence it is led to prefer bad thinking to good, to declare every momentary difficulty insoluble, and to regard every foolish mistake as revealing the bankruptcy of intellect and the triumph of intuition.

- Harsh

The natural view to take of the world is that there are things which change; for example, there is an arrow which is now here, now there. By bisection of this view, philosophers have developed two paradoxes. The Eleatics said that there were things but no changes; Heraclitus and Bergson said that there were changes but no things.

There are in Bergson’s works many allusions to mathematics and science, and to a careless reader these allusions may seem to strengthen his philosophy greatly. As regards science, especially biology and physiology, I am not competent to criticize his interpretations. But as regards mathematics, he has deliberately preferred traditional errors in interpretation to the more modern views which have prevailed among mathematicians for the last half century

Throughout Matter and Memory, this confusion between the act of knowing and the object known is indispensable. It is enshrined in the use of the word “image,” which is explained at the very beginning of the book. He there states that, apart from philosophical theories, everything that we know consists of “images,” which indeed constitute the whole universe. ... The brain, he says, is like the rest of the material universe, and is therefore an image if the universe is an image (p. 9)

Notes on An Introduction to Metaphysics

- Two kinds of knowing:

- moving round an object, dependent on point of view and symbols of expression, hence relative

- entering into an object, which does not require those things and so can be absolute.

But when I speak of an absolute movement, I am attributing to the moving object an interior and, so to speak, states of mind; I also imply that I am in sympathy with those states, and that I insert myself in them by an effort of imagination.

- That's very clear and also completely fucking obscure. It implies some kind of sympathy of internal essences, or something. I don't believe in this in the slightest, sorry. Can understand why he appeals to the WS guys though.

A representation taken from a certain point of view, a translation made with certain symbols, will always remain imperfect in comparison with the object of which a view has been taken, or which the symbols seek to express. But the absolute, which is the object and not its representation, the original and not its translation, is perfect, by being perfectly what it is.

- Well this sure is metaphysics isn't it. It almost makes sense; to the extent that the self is a a perfect absolute unity, it can reflect other unities, and know them in a sense. I just don't believe in this kind of knowledge. It seems like cryptotheism, we can perceive the world only through representations, but god sees everything for what it is and if we get this other kind of knowing under our belts, so can we.

- Counterpose one of my go-to Marvin bits (hm can't find it right now, it's the one where he scoffs at direct perception and those who think they know how it works).

- OK – but I'm trying to not be so sneery. Marvin's right from his mechanistic psychology perspective, but from an inner point of view, a person as a unitary mind has this semi-miraculous feel for the real that is more than a sum of perceptions. It might be driven by perception but the relative images are stitched up into something more objective and absolute. And while this might be unsophisticated from a computational standpoint, it describes our actual lived experience, where reality is so real to us, something shines through our imperfect and muddied windows of perception.

If there exists any means of possessing a reality absolutely instead of knowing it relatively, of placing oneself within it instead of looking at it from outside points of view, of having the intuition instead of making the analysis: in short, of seizing it without any expression, translation, or symbolic representation - metaphysics is that means. Metaphysics, then, is the science which claims to dispense with symbols.

- Will give Bergson credit for being extremely straightforward and plainspoken. That doesn't make him right though.

- OK if I try real hard: there is an reality, which we can't actually know as such, but our flickering, imperfect, relative perceptions give us hints of it, and we have this somewhat magical ability to stitch all those impressions into a model of reality, which feels pretty fucking real.

There is one reality, at least, which we all seize from within, by intuition and not by simple analysis. It is our own personality in its flowing through time - our self which endures. We may sympathize intellectually with nothing else, but we certainly sympathize with our own selves.

- Hah. I'm going to jump on that. Modern consciousness is marked by the inability to sympathize with one's own self (see Kafka, Artaud, A Case for Irony). Ironic distance from self.

When I direct my attention inward to contemplate my own self ... I perceive at first, as a crust solidified on the surface, all the perceptions which come to it from the material world. These perceptions are clear, distinct, juxtaposed or juxtaposable one with another; they tend to group themselves into objects. Next, I notice the memories which more or less adhere to these perceptions and which serve to interpret them. These memories have been detached, as it were, from the depth of my personality, drawn to the surface by the perceptions which resemble them; they rest on the surface of my mind without being absolutely myself. Lastly, I feel the stir of tendencies and motor habits - a crowd of virtual actions, more or less firmly bound to these perceptions and memories. All these clearly defined elements appear more distinct from me, the more distinct they are from each other. Radiating, as they do, from within outwards, they form, collectively, the surface of a sphere which tends to grow larger and lose itself in the exterior world. But if I draw myself in from the periphery towards the centre, if I search in the depth of my being that which is most uniformly, most constantly, and most enduringly myself, I find an altogether different thing...There is, beneath these sharply cut crystals and this frozen surface, a continuous flux which is not comparable to any flux I have ever seen. There is a succession of states, each of which announces that which follows and contains that which precedes it.

- For some reason he views perceptions, memories, etc, as static, in contrast to the flux of states beneath the surface. This just seems wrong, it's all in flux. And this emphasis on "a succession of states" – not really sure what work that is doing, but everything goes though a succession of states, doesn't it? It seems like computational language would be a lot clearer here.

Just in so far as abstract ideas can render service to analysis, that is, to the scientific study of the object in its relations to other objects, so far are they incapable of replacing intuition, that is, the metaphysical investigation of what is essential and unique in the object.

- This sounds exactly like all the other calls for magical world views the WS guys like to push, although Bergson does not use the term, "intuition" is as close as he gets to that.

- Also has some resonances with Martin Buber I/Thou now that I think about it. Technic/reason/science is I/It , Magic/intuition/holism is I/Thou.

But it [metaphysics] is only truly itself when it goes beyond the concept, or at least when it frees itself from rigid and ready-made concepts in order to create a kind very different from those which we habitually use; I mean supple, mobile, and almost fluid representations, always ready to mould themselves on the fleeting forms of intuition.

Let us try for an instant to consider our duration as a multiplicity.

- Couldn't make any sense of this section.

It is incontestable that every psychical state, simply because it belongs to a person, reflects the whole of a personality. Every feeling, however simple it may be, contains virtually within it the whole past and present of the being experiencing it, and, consequently, can only be separated and constituted into a "state" by an effort of abstraction or of analysis...Both empiricists and rationalists are victims of the same fallacy. Both of them mistake partial notations for real parts, thus confusing the point of view of analysis and of intuition, of science and of metaphysics.

- Why is that true, let alone "incontestable"? This is rampant unjustified holism. If he's just arguing that psychological models are incomplete models, well duh, all models are incomplete.

Philosophical empiricism is born here, then, of a confusion between the point of view of intuition and that of analysis. Seeking for the original in the translation, where naturally it cannot be, it denies the existence of the original on the ground that it is not found in the translation.

- This notion that empiricism invalidates personal experience is broken (but it's very common, so can't fault Bergson for arguing against it I guess, I just find it kind of tedious, are we really that confused?)

But rationalism is the dupe of the same illusion. It starts out from the same confusion as empiricism, and remains equally powerless to reach the inner self. Like empiricism, it considers psychical states as so many fragments detached from an ego that binds them together. Like empiricism, it tries to join these fragments together in order to re-create the unity of the self....But whilst empiricism, weary of the struggle, ends by declaring that there is nothing else but the multiplicity of psychical states, rationalism persists in affirming the unity of the person.

- There's some confusion about knowing-an-object-in-itself with disinterested perception. These don't necessarily have to be the same thing.

It will be noticed that an essential characteristic of the concepts and diagrams to which analysis leads is that, while being considered, they remain stationary...In any case I can, by pushing the analysis far enough, always manage to arrive at elements which I agree to consider immutable. There, and there only, shall I find the solid basis of operations which science needs for its own proper development...This means that analysis operates always on the immobile, whilst intuition places itself in mobility, or, what comes to the same thing, in duration. There lies the very distinct line of demarcation between intuition and analysis

- I don't know what he's talking about. The foundation of analysis (in the mathematical sense) is the modelling of change, and same goes for other kinds of analytical thought. The representations may be static (not really, but ok in the sense that words on a page are static) but the pheneomena they describe aren't.

- I'm getting irritated, the whole things seems like "But muh consciousness".

- For some reason thinking of that Brian Cantwell Smith paper, "The Semantics of Clocks", which has some theory as to how the temporality of the world connects with the temporality of mind.

- Alright giving up. But at the end, he enumerates some principles

I. There is a reality that is external and yet given immediately to the mind. Common-sense is right on this point, as against the idealism and realism of the philosophers.

- Aside from "immediately", OK

II. This reality is mobility. Not things made, but things in the making, not self-maintaining states, but only changing states, exist

- This is sort of the Heraclitus-Whitehead-Deleuze line of thought. I guess I don't quite see the point. Yes everything flows, but so what?

III. Our mind, which seeks for solid points of support, has for its main function in the ordinary course of life that of representing states and things. It takes, at long intervals, almost instantaneous views of the undivided mobility of the real....In this way it substitutes for the continuous the discontinuous, for motion stability, for tendency in process of change, fixed points marking a direction of change and tendency.

- Well sort of. The mind has to fix representations of things in order to operate on them, I guess. At least in the rationalist model; the embodied/situated version doesn't do that, quite explicitly. Hm. OK, it makes sense if you see him as arguing against that sort of cardboard-rationalist view of mind. Not quite what he is saying, but very resonant at least?

IV. The inherent difficulties of metaphysic, the antinomies which it gives rise to, and the contradictions into which it falls, the division into antagonistic schools, and the irreducible opposition between systems are largely the result of our applying, to the disinterested knowledge of the real, processes which we generally employ for practical ends.

- This is a kind of interesting meta-level point. I think he's saying the reason we have great wars between (eg) idealism and materialism is because both of those models are based on this kind of bad fixation he's talking about. OK, I can get behind that. And if only we realized the true nature of reality, we'd also be at peace. Hm, that sounds a bit hippie-dippy to me. Certainly Heraclitus believed not just in the universal flow, but the importance of conflict.

V But because we fail to reconstruct the living reality with stiff and ready-made concepts, it does not follow that we cannot grasp it in some other way.

VI It [our intelligence] can place itself within the mobile reality, and adopt its ceaselessly changing direction; in short, can grasp it by means of that intellectual sympathy which we call intuition. This is extremely difficult. The mind has to do violence to itself, has to reverse the direction of the operation by which it habitually thinks, has perpetually to revise, or rather to recast, all its categories. But in this way it will attain to fluid concepts, capable of following reality in all its sinuosities and of adopting the very movement of the inward life of things.

- Did he actually have techniques for this difficult task? Like, practices to make the mind more flowy? Hey, I'm ready to do violence to my own mind, any time!

- I can see why this guy was popular; he has a bit of cult-leader thing going in here.

VII. This inversion has never been practised in a methodical manner; but a profoundly considered history of human thought would show that we owe to it all that is greatest in the sciences, as well as all that is permanent in metaphysics.

Having then discounted beforehand what is too modest, and at the same time too ambitious, in the following formula, we may say that the object of metaphysics is to perform qualitative differentiations and integrations.

- solve et coagula?

IX. The whole of the philosophy which begins with Plato and culminates in Plotinus is the development of a principle which may be formulated thus: "There is more in the immutable than in the moving, and we pass from the stable to the unstable by a mere diminution." Now it is the contrary which is true. Modern science dates from the day when mobility was set up as an independent reality. It dates from the day when Galileo, setting a ball rolling down an inclined plane, finnly resolved to study this movement from top to bottom for itself, in itself, instead of seeking its principle in the concepts of high and low, two immobilities by which Aristotle believed he could adequately explain the mobility.

- Oh that's interesting. OK, I understand better what he is arguing against (Platonism, more or less?)

The Physicist and the Philosopher

- book by Jimena Canales, a good overview of Einstein debate

For the rest of his life, Whitehead explicitly fought against the bifurcation of nature into dualistic camps (that of physics and psychology, matter and miond, and ohters)...his answer to the impasse consisted in crafting a philosophy that denied a distinction between nature and experience: (p188)

- George Herbert Mead tries to reconcile Bergson and Einstein p197

Random Links

- Acid Horizon: Matter and Memory: An Intro to Henri Bergson with Jack Bagby on Apple Podcasts

- I listened to this in frustration, no idea wtf this was about.

- Philosophy Bites podcast with Emily Herring (biographer)

- His enchanting, musical lecturing style. No notes.

- Bergson had an alternative to mechanistic model of universe/mind. He had a background in math (somewhat surprising) and solved some hard problems. He was very familiar with science of the day, including evolution.

- He started off as mechnist, but the spatialization of time somehow threw him?

- Négritude (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

Donna Jones rightly speaks of Negritude as an “Afro-Bergsonian epistemology”. (Jones, 2010)